Navigating Truth in the Age of Disinformation: A Scientific Perspective

Written on

Chapter 1: The Nature of Truth and Science

In today's world, the concept of truth seems to be more subjective than ever. Consider a hypothetical exchange between two colleagues at work:

A: My parents finally got their COVID vaccine, but I’m still waiting.

B: That’s unfortunate! Do you think you’ll get it soon?

A: Are you planning to get yours this month?

B: Absolutely not! I refuse to put that in my body.

A: But don’t you think you should get vaccinated?

B: Have you heard about the deaths caused by the vaccine?

A: Actually, I believe there have been zero deaths linked to it.

B: No way! I read online that there are many deaths. I don't want to be one of them.

A: Just a reminder, over 400,000 people in the U.S. have died from COVID. Maybe you should be more worried about that than the vaccine.

B: The truth is no one really knows. You believe what you want, and I’ll stick to my beliefs. I think the vaccine is more dangerous than COVID, which might even be a hoax.

While this conversation is fictional, it reflects a troubling reality. What constitutes truth in our society? Do we genuinely believe that everything is true? Consider the moon landing in 1969—was it genuine, or a staged event? Some argue against evolution, asserting that humans cannot be related to primates. Others claim the Earth's average temperature is falling, attributing changes to solar activity. And then there are those who insist the Earth is flat, or even that Elvis is still alive.

We currently live in an era where every idea can find a platform. But how does this relate to scientific understanding?

Truth and the Essence of Science

One of the core challenges is that science does not provide absolute truths; instead, it constructs models. We can never fully grasp what is "true." As Indiana Jones aptly stated, "Archeology is the search for fact, not truth." If you seek truth, Dr. Tyree’s philosophy class is where you should go.

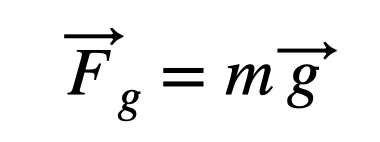

So, what is a model? Let's take gravity as a case in point. In introductory physics, the gravitational force is defined as:

This equation indicates that gravitational force is a vector that aligns with the gravitational field (g) and has a magnitude equal to the product of g and mass. The gravitational field is measured at 9.8 Newtons per kilogram. However, this is not "the truth"; it's merely a model—albeit a useful one. If you were to travel to the moon, you'd require a different model for gravitational interactions.

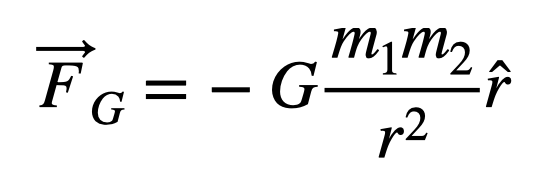

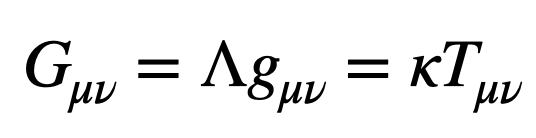

This model illustrates that gravitational force diminishes with distance from a planet or moon. While it’s a more accurate representation, it still doesn’t equate to the absolute truth. Einstein’s Field Equation provides more detail, yet it remains just a model.

Science is limited in its ability to prove truths; however, it can disprove ideas. For instance, if someone insists that the Earth is flat, and I present evidence that contradicts that belief, I effectively debunk it.

Take a look at the image at the beginning of this article, which captures a view of New Orleans across a lake. Notice how you can see the tops of buildings, not their bases. Why is that? It’s a result of the Earth's curvature. If the Earth were flat, our view would be different—although some might argue that the lake has a slight bulge.

Communicating Scientific Ideas

Another hurdle is that scientific ideas cannot exist in isolation; they require collaborative dialogue and development. The stereotype of a scientist toiling away alone in a lab is misleading. Scientists exchange ideas through publications, conferences, and other forums.

Ideas undergo a vetting process. In peer-reviewed journals, experts assess submissions for credibility. While this system is not flawless, it does provide a level of scrutiny.

Consider a conference presentation featuring a fringe idea—like the flat Earth theory. It’s unlikely such a concept would gain traction in a peer-reviewed journal, yet it could spread easily through platforms like YouTube or blogs, where sharing information is as simple as clicking a button.

This accessibility means that anyone can find support for their beliefs, regardless of their validity. The abundance of information can be overwhelming, akin to a buffet of ideas. So how do we discern credible information from misinformation? This is not a straightforward task. Fortunately, several fact-checking websites, such as FactCheck.org, Snopes.com, and Politifact.com, aim to verify claims. Even Wikipedia has become a valuable resource for checking facts.

As we navigate this era of disinformation, it’s crucial to differentiate between harmless beliefs, like the flat Earth theory, and more concerning misconceptions, such as climate change denial or COVID-19 skepticism, which can have significant societal implications.

Chapter 2: The Impact of Misinformation

In this chapter, we will explore how misinformation affects public perception and policy decisions, emphasizing the importance of critical thinking in scientific discourse.

The first video, "Not Every Idea is Worth Your Time as an Entrepreneur," discusses the importance of discerning valuable ideas in a sea of misinformation.

The second video, "How to Get and Evaluate Startup Ideas | Startup School," provides insight into assessing the viability of ideas in the entrepreneurial landscape.