Life Expectancy Disparities: Exploring Social Determinants

Written on

Chapter 1: Understanding Life Expectancy Variation

Recent research highlights significant disparities in life expectancy linked to social determinants of health.

Consider two individuals in the U.S. celebrating their 30th birthdays. On one hand, we have a married white woman with a university degree; on the other, a never-married white man who only completed high school.

How many additional years can each expect to live? The difference is stark. The male's life expectancy averages 37.1 more years, projecting him to live until approximately 67, while the woman is expected to reach 85. This results in an 18-year gap in life expectancy, influenced by gender, education, and marital status.

These examples illustrate the extremes in life expectancy shaped by four critical social determinants: sex, race, marital status, and education. While many are aware of these influences on health, recent studies suggest a more complex landscape than previously understood.

I must acknowledge my own perspective here. As a clinical researcher, I occasionally struggle to grasp the implications of actuarial studies that compare life expectancy across demographics defined by marital status. The conclusion that married individuals live longer raises questions: Should I advise my patients to marry? The findings that women typically outlive men or that white individuals have a longer lifespan compared to Black individuals pose similar dilemmas for me. These are factors beyond immediate control. My efforts are better spent encouraging healthier lifestyles, such as quitting smoking or improving diets.

Nonetheless, examining these groups provides a foundation to explore more relevant inquiries. Why do women generally outlive men? Is it due to behavioral differences, such as men taking more risks or avoiding medical consultations? Or could hormonal factors, like the protective effects of estrogen versus testosterone, play a role?

Integrating these social determinants into a coherent narrative proves to be more challenging than it appears, as highlighted in a study published in BMJ Open.

Chapter 2: The Study Overview

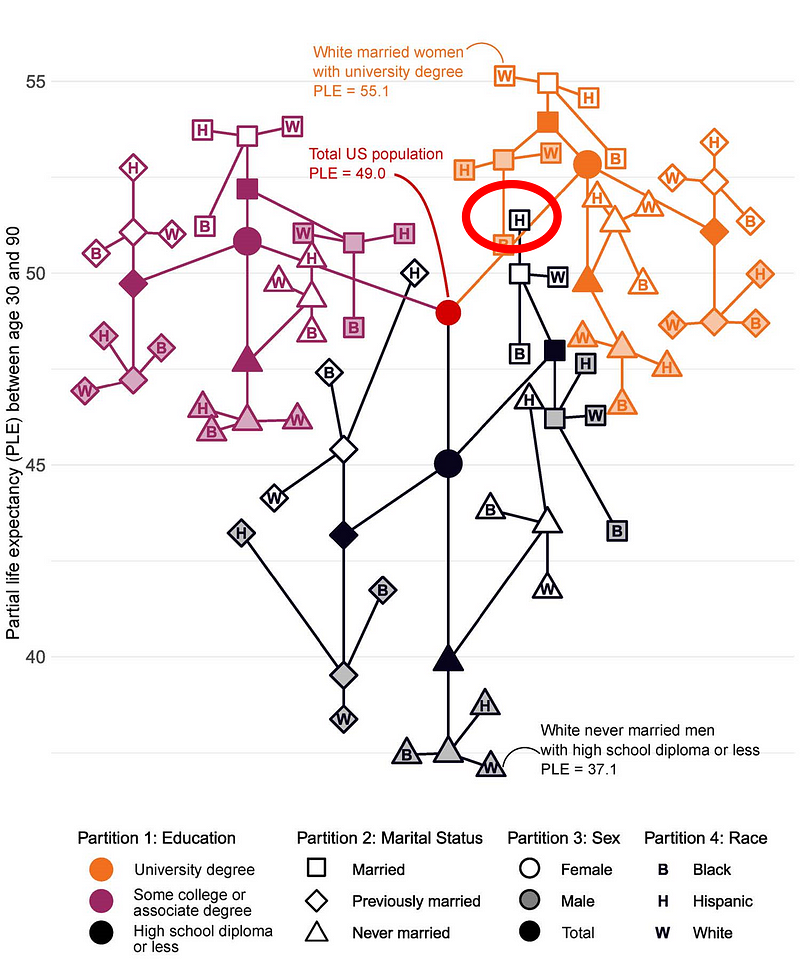

In the context of the research, each American can be categorized into one of 54 distinct groups based on sex, race, education level, and marital status.

While this classification doesn't fully encapsulate the rich diversity of American life, the researchers utilized data from the American Community Survey, which includes 8,634 individuals, making finer distinctions difficult.

The survey results were population-weighted to accurately reflect the broader U.S. population. The data collected on the aforementioned categories was then linked to the CDC's Multiple Cause of Death dataset.

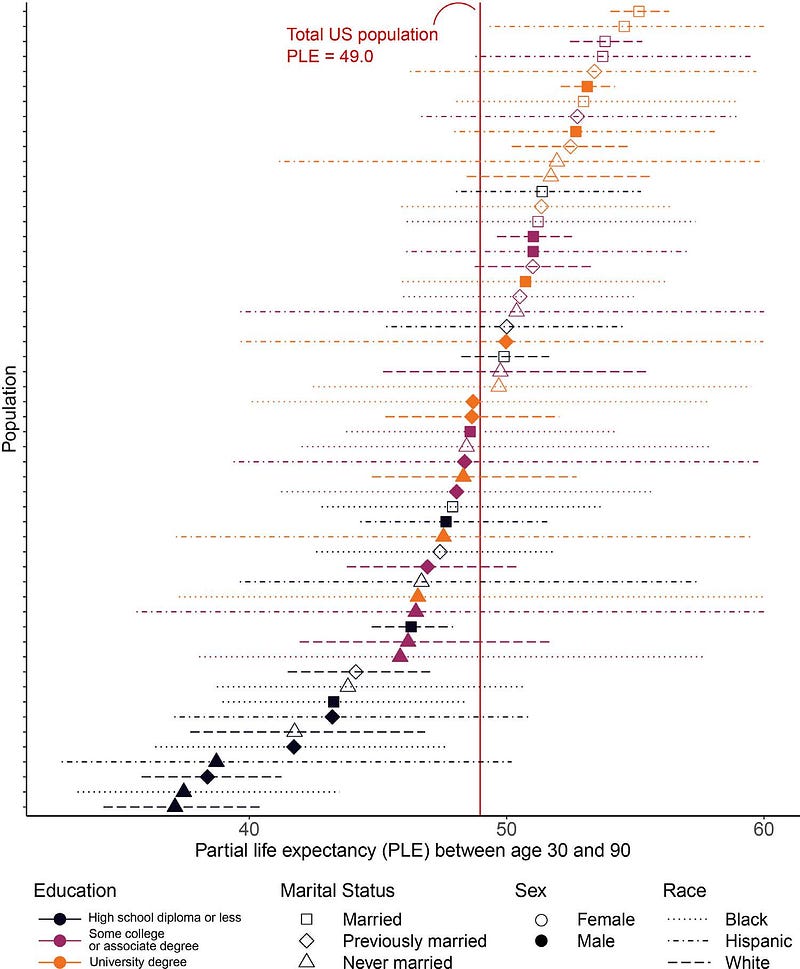

From here, the researchers could rank the 54 groups by life expectancy, revealing notable variations.

However, the most intriguing aspect of this study lies not in the ranking itself but in the inconsistent messages that emerge across these categories.

To illustrate this point, let’s examine another figure from the paper, which highlights the unexpected diversity within these life expectancies.

While it may seem complex, the higher points on the Y-axis indicate groups with longer life expectancies. For instance, groups with a high school education or less (represented in black) generally show lower life expectancies. However, there are exceptions; married Hispanic women with lower education levels exhibit favorable life expectancy outcomes.

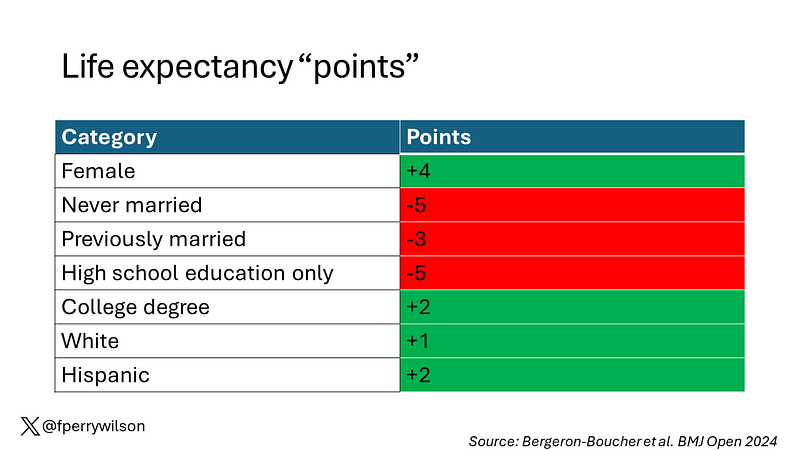

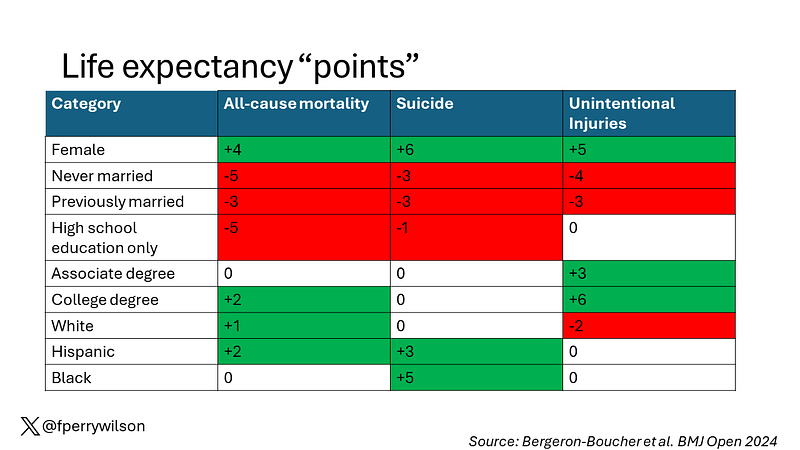

The authors quantify these findings through a mortality risk score, where a score of zero represents average mortality in the U.S.

This scoring system reveals that being female is advantageous for longevity, while being unmarried poses a risk. Education significantly impacts life expectancy, with those holding a college degree benefitting from a higher score, while those with only a high school diploma face penalties. Race appears to play a relatively minor role in this scoring.

While the findings are fascinating, they are not particularly actionable for me as a physician. The more pressing question is understanding the reasons behind these disparities, which the study data begins to address—particularly through an analysis of causes of death.

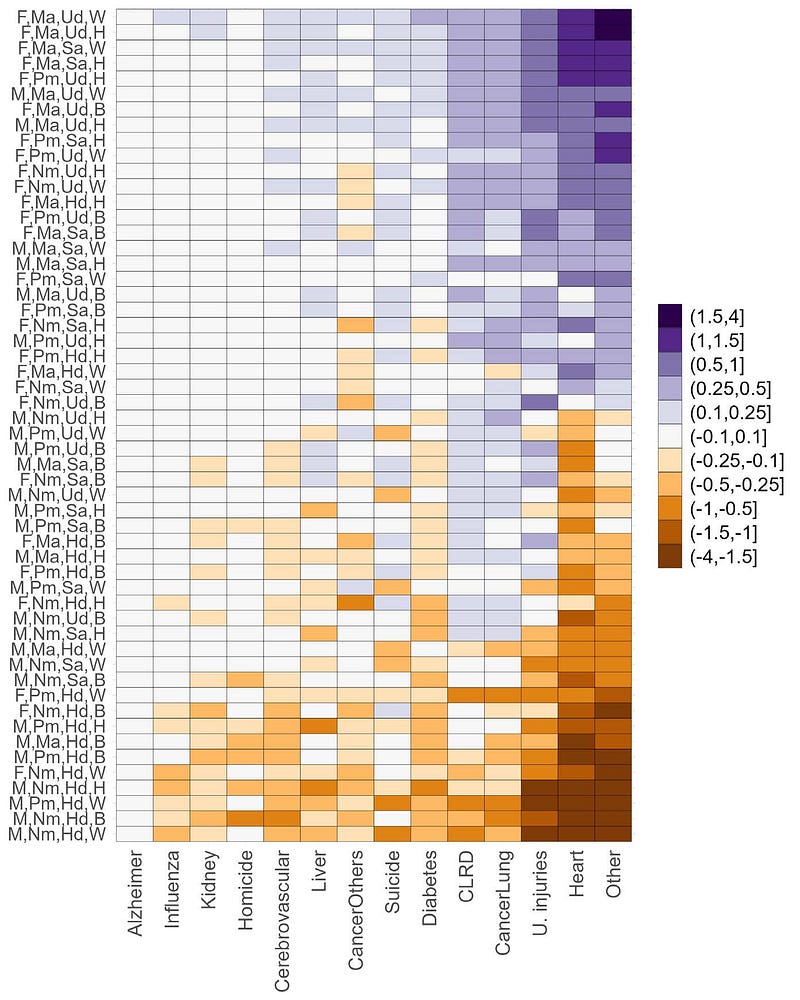

In the following figure, the 54 groups are ranked again, highlighting the likelihood of dying from various conditions relative to the general population.

The lower-ranked groups exhibit significantly higher risks of death from unintentional injuries, heart disease, and lung cancer, along with increased suicide rates. In contrast, higher-ranked groups show no unexpected risk, aside from a notable instance concerning "other cancers," which reveals that many cancers do not adhere to socioeconomic boundaries.

We can further refine the risk scoring system to reflect the likelihood of different causes of death.

This analysis suggests that white individuals, despite lower overall mortality, face heightened risks from unintentional injuries compared to other groups.

Ultimately, examining causes of death may provide insights into the underlying reasons for these disparities. However, this study is just a starting point. It should prompt us to recognize that, in a nation as affluent as the United States, such stark disparities exist due to factors that, aside from sex, are largely non-biological. Consequently, to uncover the reasons behind these differences, we may need to shift our focus from physiology to sociology.

The first video, "Sex, Race, Marital Status, Education: Four Factors that Add Up to 18 Years of Life Expectancy," delves into these determinants and their profound impact on lifespan, offering a closer look at the study's findings.

The second video, "Proving the Superiority of Capitalism... With Genetics?" explores how economic systems intersect with health disparities, providing additional context to the ongoing discussion about life expectancy.

A version of this commentary first appeared on Medscape.com.