Exploring the Fascinating Science of 1879: A Historical Perspective

Written on

Chapter 1: A Discovery in Time

During a leisurely vacation afternoon, I stumbled upon a quaint used bookstore. Amidst the familiar cookbooks and romance novels, I discovered a rare gem: an 1879 textbook titled A Natural Philosophy by G. P. Quackenbos, LL.D. Holding this piece of history in my hands, I felt a thrill of excitement, as it represents a significant moment in the evolution of scientific knowledge. The price? A mere $1.50. As a history enthusiast and science lover, this book has become my most treasured possession, offering a captivating glimpse into the scientific understanding of the late 19th century.

Fun with Cadavers

Science is inherently a human pursuit, often revealing its darker aspects. Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, published in 1818, may have been inspired by actual experiments like those detailed in the Quackenbos textbook. In the chapter entitled "Physiological Effects of Voltaic Electricity," the author describes:

A few years back, the body of a convicted murderer executed in Glasgow was subjected to an electrical experiment approximately 75 minutes post-execution. Using a battery with 270 pairs of four-inch plates, one electrode was applied to the spinal cord at the neck, and the other to the sciatic nerve in the left hip, causing the entire body to convulse violently, reminiscent of a shiver. Adjusting the wires produced dramatic effects, such as heaving the chest and creating bizarre facial expressions.

The author’s intention to engage the reader is clear. The fascinating effects of electricity on biological tissues were crucial for our current understanding of muscle movement and sensory perception. Yet, I can't help but question the motivations of the Glasgow experimenters. It seems unlikely they uncovered any new insights; a century earlier, Luigi Galvani had already demonstrated that chemical-induced electricity could cause dead frog legs to twitch. It feels more plausible that the experiment was conducted for amusement, possibly aided by alcohol.

The Victorian Heat Ray

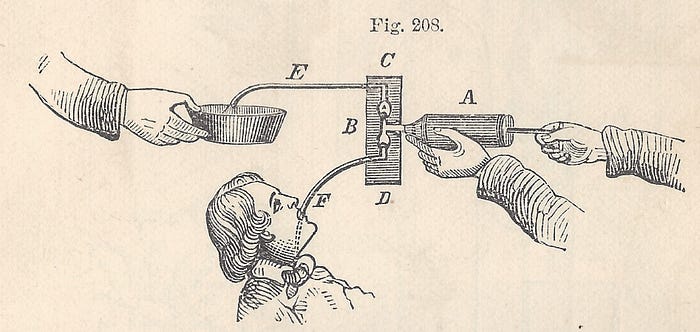

Quackenbos demonstrates an understanding of infrared radiation, although the term itself is notably absent. Instead, he refers to it as radiant heat. The subsequent text and accompanying diagram illustrate that, in 1879, scientists recognized an invisible form of light could traverse space and be focused by parabolic mirrors.

Quackenbos states:

The reflection of radiant heat can be illustrated with the apparatus shown in Fig. 213. Concave metallic mirrors A and B are polished, with a red-hot ball C placed at the focus of A. This ball emits heat in every direction, with some rays reflecting off mirror A in parallel lines toward B. They are then reflected again to a focus at D, where a thermometer detects an increase in temperature. This setup can generate enough heat at D to ignite phosphorus or gunpowder.

This description presents a device capable of transmitting a genuine heat ray through the air to ignite a distant object! While not as advanced as today’s laser technology, such knowledge could have influenced the Martian heat rays depicted in H. G. Wells’ War of the Worlds (1897).

The Birth of Electrical Machinery

In 1820, Hans Christian Ørsted discovered the link between electricity and magnetism, which laid the foundation for the future electronics revolution. A Natural Philosophy outlines these recent electromagnetic advancements for its readers. For instance, Quackenbos illustrates how to magnetize a horseshoe-shaped piece of metal using a battery-operated electromagnet.

One of the most transformative electrical innovations of this era was the telegraph, enabling instantaneous global communication. For the first time, messages could traverse the globe in mere minutes instead of weeks. The textbook devotes extensive discussion to the history and mechanics of telegraph systems.

Yet, significant hurdles remained before electric motors could be widely utilized. While electric motors existed in 1879, they were largely impractical due to the high costs of generating sufficient electricity. Quackenbos explains:

A 28-foot boat carrying twelve people was propelled against the current at three miles per hour through electromagnetic means. Similarly, a locomotive reached speeds of ten to twelve miles per hour. However, the operational costs of maintaining the galvanic battery exceeded those of generating steam. Until these challenges are addressed, electromagnetism cannot be effectively employed as a mechanical force.

It would take several more decades for advancements in generators, turbines, and electrical grids to render electric motors viable for industrial and domestic applications.

Surprises from Powerful Magnets

In discussing scientific experiments with powerful electromagnets, Quackenbos uncovers an intriguing finding: certain materials previously thought to be magnetically inert exhibit minor reactions to intense magnetic fields.

He classifies substances attracted by magnets as magnetic and those repelled as diamagnetic. I found it particularly surprising to read:

Similar tests can be conducted on liquids and gases when enclosed in tubes. Oxygen is magnetic, whereas water, alcohol, ether, and oils are diamagnetic.

Before this revelation, I was unaware that water could be repelled by magnets! This prompted me to conduct my own experiments, such as using a magnet to push a grape. It’s amusing to think that a book over 140 years old could teach me something new about physics!

Astronomical Measurements

Comparing the astronomical knowledge of 1879 to today’s understanding is fascinating. While Pluto would not be discovered until 1930, the major planets were already recognized.

I compared the data table below with modern values, noting a mixture of impressive accuracy alongside significant errors.

The distances of the planets from the Sun were relatively well understood, owing to observations of Venus transiting between the Earth and Sun, which allowed astronomers to measure the Solar System using terrestrial distances. However, the values in the table are about 1.7% lower than current measurements.

Planetary diameters were mostly accurate, with Earth's diameter being especially precise at 7926 miles. While Mars and Neptune had discrepancies of 8% and 19% respectively, the inaccuracies are understandable given Neptune's extreme distance.

What truly baffles me, however, is the erroneous sidereal day measurements. For instance, the claim that Venus rotates every 23 hours, 16 minutes, and 19 seconds is not only incorrect but absurd!

Covered by dense clouds, Venus’s surface is not visible through optical telescopes. Yet, according to the textbook, early observers mistakenly believed they could see variations on its surface:

So intense is its brightness that variations in its surface (if indeed its surface is not hid from us by a cloudy atmosphere) for the most part escape detection, every portion of the disk being flooded with light. Yet spots have occasionally been seen on its surface, and mountains have been observed having an estimated height of 15 to 20 miles.

Today, we know Venus rotates once every 243 days, in the opposite direction of most planets. The precision of the earlier claim (to the second!) is astonishing, especially given the lack of observational basis.

Quantum Insights

Sometimes we are aware of our ignorance, while other times, we remain oblivious to what we don't know. This ambiguity is evident in certain sections of A Natural Philosophy, particularly regarding quantum mechanics. Although this book predates Max Planck's quantum hypothesis, it hints at emerging ideas. One passage on optics states:

If solar light is analyzed with a spectroscope, numerous dark lines can be observed crossing its surface.

These lines maintain consistent positions in the solar spectrum, but vary in number and arrangement when analyzing starlight. The spectra of burning metals like iron and sodium have bright lines that correspond to some of the dark lines in the solar and stellar spectra. It is understood that metallic vapors absorb the rays they emit, suggesting the presence of these metals in the atmospheres of the sun and stars.

Although atoms were known in 1879, the concept of subatomic particles like electrons was not yet established, making it impossible to explain spectral lines. There is no mention of these lines as an unresolved mystery; the author simply presents them as facts. This raises questions about Quackenbos’s curiosity. Did he think, "that’s just how things are," or did he ponder them in silence?

I try not to be overly self-satisfied. The same could be true for our time. What subtle hints are we overlooking? What questions haven’t we even considered?

I can envision someone 140 years from now perusing a contemporary science textbook. The knowledge we take for granted may be unfathomable to them. I hope they appreciate our creativity and, like me, discover something valuable.

Chapter 2: Learning Science from an Educator's Perspective

The first video, titled "What is Learning Science from an Educator's Perspective?" delves into the principles behind effective science education and the methods educators use to engage students in the learning process.

Chapter 3: The Year 1879 in Science

The second video titled "1879 in Science | Wikipedia Audio Article" provides an audio overview of significant scientific advancements and events that took place in the year 1879, showcasing the era's contributions to the field.