Understanding the Dunning-Kruger Effect in Everyday Life

Written on

Chapter 1: The Paradox of Confidence

Imagine yourself on a deserted island, reminiscent of the famous TV series Lost. After gathering some basic supplies and setting up a shelter, you embark on a quest for food. In a surprising turn of events, you discover a shark trapped in a tide pool. With some sharpened sticks, you manage to catch it and return to your base, dreaming of a hearty shark soup for dinner.

“Wait a minute,” interjects a fellow survivor, a college professor. “I think we should reconsider. I’ve heard that some parts of sharks can be toxic.”

“Poisonous?” retorts another survivor, a sunburned man boasting about his outdoor skills. “Sharks are predators—they can’t be poisonous! I’ve caught plenty of fish, and we should eat this shark!”

In this scenario, the second survivor appears more confident, while the professor, despite his knowledge, seems less assured. Who should you believe? Is eating the shark a safe choice?

Interestingly, you don't need to be on a deserted island to face such dilemmas. Online discussions often reveal that it's not the experts who are the most vocal or confident; it's frequently the novices who, despite their limited knowledge, assert that they know best.

Consider this: who’s more certain about a strange noise in your car—the experienced mechanic or your friend who's only changed his oil a couple of times? Who believes they can enhance workplace dynamics more—the seasoned employee or the rookie fresh out of college? Conversely, have you witnessed someone deliver an excellent performance yet express doubt about their success?

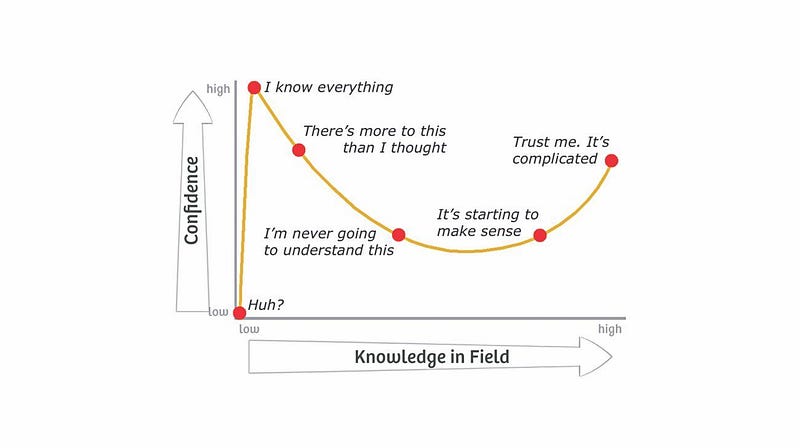

This discrepancy between confidence and ability is a well-documented phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect. Named after two psychologists who explored this concept, it suggests that individuals often struggle to recognize their own lack of competence.

It’s illustrated in a graph:

Many of us have felt this phenomenon firsthand. For instance, when I began programming, I was brimming with confidence, convinced I could tackle any coding challenge with just a cup of coffee and a couple of hours of work. Years later, though my skills have improved, I no longer assume I can solve every problem instantly.

This effect can manifest in various fields—from a novice mechanic examining a complicated engine to someone out of shape trying to get fit, or a WebMD user confidently diagnosing a condition. Ironically, those who are more educated tend to feel less confident and are less likely to assert themselves as experts. The more we learn, the more we become aware of our limitations.

Chapter 2: Recognizing Dunning-Kruger in the Workplace

You don't need to be on a deserted island to witness the Dunning-Kruger effect; it’s prevalent in many workplace scenarios. Consider the following statements often heard in office settings:

“Trust me, I know exactly how this works! I once skimmed the cover of a book about it!” “Look, you said this would take six weeks—just make it happen faster!” “I just completed a course, so I’m an expert now!” “This new phone is malfunctioning! It’s not doing what I expect!” “I’m the best in my office at this, so I know how it works!” “You may have advanced qualifications, but I’m pretty sure I know more than you.” “Of course, I can manage this multi-million dollar project—I’ve handled small ones before; it’s probably the same.”

These statements exemplify the Dunning-Kruger effect, or more broadly, illusory superiority, where individuals overestimate their abilities.

Fortunately, there are strategies to combat this tendency—awareness is key.

Section 2.1: Strategies for Self-Assessment

To mitigate our own overconfidence, consider the following steps:

- Assess your experience relative to industry standards. If you've only been using a saw for two weeks, it’s unlikely you have the same expertise as a master carpenter.

- Seek a second opinion from an expert and genuinely consider their advice. If an expert suggests a project will take significantly longer than you anticipated, take that insight seriously.

- Acknowledge that there’s likely more you don't know. If you believe you have complete knowledge about a subject, that should raise a red flag. True experts are aware of their own limitations.

Section 2.2: Guiding Others Gently

When faced with someone overly self-assured, it’s challenging to sway their opinion directly, but you can subtly guide them:

- Recommend adding extra time to their schedule and share instances from the past where this would have been beneficial.

- Encourage them to seek expert opinions, particularly from someone with authority. This approach might work better with a colleague than a superior.

- If all else fails, ensure that all plans are documented. If your boss outlines an unrealistic plan, you can track deviations from reality over time.

- Foster an environment where experts feel empowered to speak up. While the Dunning-Kruger effect suggests that the uninformed tend to be the loudest, it also indicates that knowledgeable individuals might hesitate to assert themselves.

Ultimately, we must avoid conflating confidence with expertise. The person who expresses their thoughts most assertively isn’t always the true expert; the real expert is the one who can substantiate their claims with credible evidence.

Even David Dunning, co-creator of the Dunning-Kruger effect, has admitted to falling victim to it. Despite using an inhaler for 15 years, he realized he was not using it correctly, having assumed he understood it without consulting the instructions.

In conclusion, we must remain vigilant about recognizing the Dunning-Kruger effect in ourselves and others. Are we aware of our knowledge gaps? Can we cite specific experiences that inform our beliefs? Do we acknowledge our limitations? Are we overly confident to mask our uncertainty?

The same scrutiny should be applied to others. What credentials do those making confident assertions possess? Are their claims backed by evidence? Setting aside confidence, does their plan hold up?

Every day, we run the risk of assuming that high confidence equates to substantial knowledge. It's crucial to recognize our own blind spots, as we often overlook our inadequacies, especially when pointed out by others. The only remedy is to stay alert, and if we possess the knowledge to support our statements, we should be brave enough to voice them.

Sam Westreich, who holds a PhD in genetics, specializes in studying the gut-associated microbiome. He currently works at a bioinformatics startup in Silicon Valley. Follow him on Medium or Twitter at @swestreich.

Have a science-related question? Feel free to comment with your suggestions for future topics. Also, check out this related article:

Starting a New Job: Embracing the Challenges

Beginning a new job can be stressful, intimidating, and frustrating—but it’s a natural part of growth. Here are ways to navigate those feelings effectively.

The first video titled "Why Smart People Are Not Always Successful" explores why intelligence doesn't always lead to success.

The second video, "4 Things Emotionally Intelligent People Don't Do," discusses behaviors to avoid for emotional intelligence.