Is Pseudo-Philosophy a Reality Alongside Pseudo-Science?

Written on

Chapter 1: Introduction to Pseudo-Science

In contemplating the existence of pseudo-science, one might wonder if pseudo-philosophy exists as well.

Back in 1995, after completing my postdoctoral year at Brown University, I relocated to Knoxville, Tennessee, to embark on my first tenure-track role as an assistant professor specializing in botany and evolutionary biology. My knowledge of Tennessee was minimal, mostly shaped by advertisements for Jack Daniel's whiskey in Italy. Eager to establish my laboratory focused on plant evolutionary genetics, I looked forward to mentoring graduate students and integrating into the local community, often referred to as K-town.

However, I had not anticipated that Tennessee is known as the “buckle” of the Bible Belt, where nearly 90% of the populace subscribes to creationism and dismisses evolution. I soon found that my neighbors viewed me as somewhat peculiar, and some of my undergraduate students cautioned their peers that attending my lectures could lead them to Hell. My local prominence grew through media coverage, prompting polite inquiries from strangers in bookstore parking lots about whether I had read the Bible. When I inquired if they had ever engaged with The Origin of Species, they reacted with astonishment.

During my second semester, the Tennessee state legislature, in a display of misguided judgment, proposed a bill mandating “equal time” for teaching evolution and creationism in high schools. My incredulity at the article prompted me to think, “What?!?” The BBC covered the unfolding story, and several colleagues and I reached out to our representatives to articulate the folly of such legislation. Fortunately, the bill did not advance beyond committee, but it sparked my commitment to educating the public. I organized a summer trip to Dayton, the site of the infamous Scopes trial in 1925, and initiated an annual Darwin Day event with colleagues and graduate students, aimed at enlightening the community about science and its relationship with religion. This initiative has since gained international recognition.

This experience ignited my interest in pseudo-science, which I explored through public lectures and writings for various publications, notably Skeptical Inquirer. My engagement with this topic led to the publication of two books: Denying Evolution, focusing on creationism, and Nonsense on Stilts, which examines pseudo-science in a broader context.

A few years later, I began transitioning into philosophy, enrolling in a PhD program at the University of Tennessee. This eventually culminated in my 2009 appointment as a professor of philosophy of science at the City University of New York, where I continue to work today. A central theme of my scholarly pursuits has been the nature of pseudoscience and the so-called demarcation problem between science and pseudoscience. This research has resulted in two academic publications: The Philosophy of Pseudoscience and Science Unlimited?.

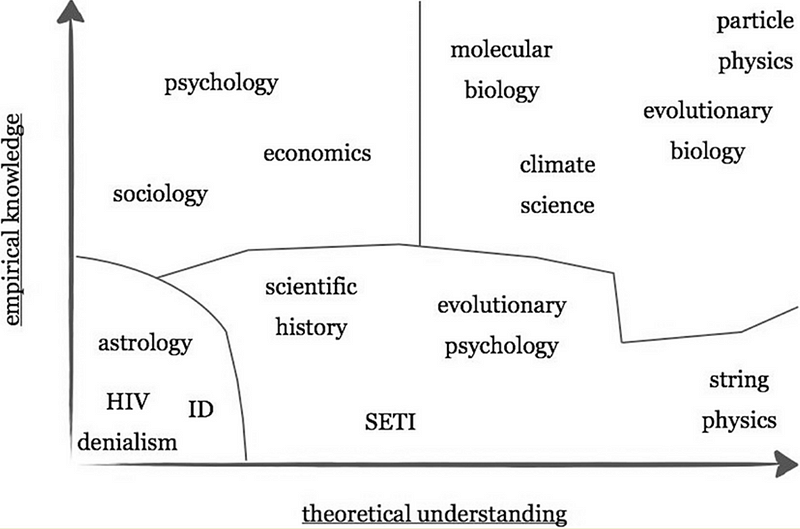

The prevailing view in the philosophy of science suggests that no straightforward distinction exists between science and pseudoscience. Instead, the situation resembles a conceptual landscape illustrated in the following diagram:

To orient ourselves: the horizontal axis measures theoretical sophistication, while the vertical axis gauges empirical content. The premise is that the higher a discipline ranks on both axes, the more firmly it is established as science. Clear examples include fundamental physics, chemistry, and biology. Conversely, fields scoring low on both axes are typically classified as pseudoscience, such as astrology, intelligent design creationism, and the notion that HIV does not cause AIDS.

This should be uncontroversial, particularly outside the Bible Belt. However, the more intriguing areas lie in the middle of the diagram. Some fields may lack theoretical depth but possess considerable empirical richness, such as psychology. Conversely, others, like string theory in physics, might be highly sophisticated theoretically yet lack substantial evidence. Neither category qualifies as pseudoscience, yet they do not fully embody the rigor of established science.

Consider the case of SETI, the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, where theoretical sophistication is minimal—merely relying on the assumption that extraterrestrials share a psychology and technological history akin to our own—and empirical evidence is virtually non-existent thus far. Nearby, we find actual pseudosciences, such as parapsychology, which, while not as blatant as astrology or creationism, still exhibit scant evidence and weak theoretical frameworks.

An additional complexity arises, not represented in the diagram: the conceptual map evolves over time, suggesting a third axis extending from the page. For example, astrology and alchemy were once respected scientific pursuits, endorsed by figures like Ptolemy and Newton, but are now firmly categorized as pseudoscience. My colleague Maarten Boudry and I refer to this phenomenon as the “pseudoscience black hole”: once a discipline crosses into pseudoscience territory, it rarely returns to legitimacy, and we have struggled to find historical instances of such a resurgence.

Over time, I have been introduced to a wide array of modern philosophical concepts, some invigorating, others perplexing, and some downright bizarre. This exposure has led me to consider that, similar to the science-pseudoscience dichotomy, one can envision a blurry boundary between philosophy and pseudo-philosophy.

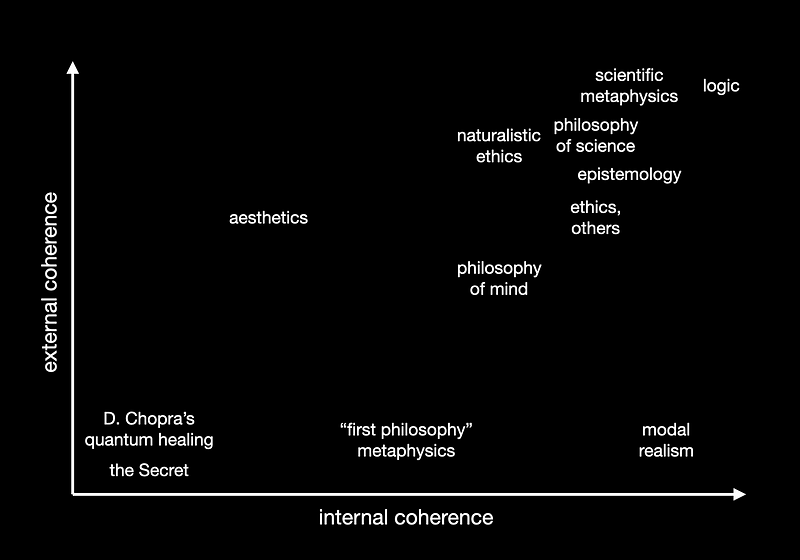

While my thoughts on this topic are not yet fully formed, let’s begin by sketching a diagram akin to the previous one to illustrate my perspective on the philosophy versus pseudo-philosophy conceptual landscape. This time, the horizontal axis will represent internal coherence, as philosophical accounts must avoid contradictions or inconsistencies. The vertical axis will denote “external coherence,” which reflects how a philosophical idea aligns with our understanding of the world, particularly as informed by scientific knowledge.

Why should philosophers prioritize external coherence? I argue that philosophy is a hybrid inquiry type, grappling with conceptual issues akin to logic or mathematics, while also addressing how the real world operates, resembling scientific inquiry. Philosophical progress hinges on exploring conceptual landscapes, yet such exploration must be anchored in empirical evidence. For example, developing alternative ethical frameworks, such as virtue ethics, Kantian deontology, or utilitarianism, must consider their applicability to real human experiences, as frameworks devoid of utility are less compelling.

This second diagram, while less complete and more tentative than the first, reflects my current thinking. Future iterations may evolve based on feedback. For now, let's delve into it to clarify my propositions.

Starting with the straightforward cases: in the upper right quadrant, we find philosophical domains characterized by both high internal and external coherence, such as logic, scientific metaphysics, philosophy of science, and epistemology. Philosophical constructs within these fields are both well-articulated and informed by relevant scientific insights.

Conversely, in the lower left quadrant, we identify clear instances of pseudo-philosophy. For example, Deepak Chopra's "quantum healing" (or, essentially, much of his work) exemplifies this, along with the absurd notion presented in "The Secret," which claims that the universe will reshape itself to fulfill your desires if you wish hard enough.

As with the science versus pseudoscience diagram, the middle ground is more intriguing. For instance, I believe naturalistic approaches to ethics, like virtue ethics, exhibit slightly less internal coherence than traditional frameworks such as Kantianism and utilitarianism. However, this deficiency is counterbalanced by their greater alignment with human nature and behavior.

Modal realism, the idea that all logically possible worlds exist in the same way our world does, presents an internally coherent yet completely disconnected concept from our empirical understanding. The philosophy of mind is a well-established field, but its engagement with neuroscience may be diminishing, especially for those who view the endeavor with skepticism.

Aesthetics draws significant input from empirical data concerning human perceptions of beauty and ugliness, yet it suffers from a plethora of accounts that, at least from my perspective, do not correlate well with empirical evidence.

Finally, we arrive at the contentious area of "first philosophy" metaphysics, which I have previously discussed. This remains a dominant approach to metaphysics, despite the perception that it should have ceased to exist centuries ago, with Descartes. "First philosophy" refers to inquiries concerning the fundamental nature of reality, historically based on reason alone. Its lineage extends from the pre-Socratics to Descartes himself. Yet, Descartes’ thought experiment involving a deceptive demon illustrated that reliable knowledge of reality cannot arise without empirical evidence. Countless logically coherent possible worlds exist, and the only means to discern the actual one is through observation and experimentation (unless, of course, you subscribe to modal realism).

First philosophy emerged concurrently with the birth of modern science, as Descartes was a contemporary of Galileo. This led to the development of scientific metaphysics, which seeks to unify insights from diverse scientific disciplines into a coherent understanding of the cosmos and our position within it.

Despite this, first philosophy continues to thrive, evidenced by David Chalmers’ philosophical zombies, which offer no insights into consciousness; Philip Goff’s fanciful notions of panpsychism; and Nick Bostrom’s speculations about living in a simulation and advocating for extensive global surveillance.

Is first philosophy, often referred to as analytic metaphysics, pseudo-philosophy? If not, it certainly approaches that classification, paralleling the precarious position of SETI and parapsychology within the science versus pseudoscience framework. Yet, can we assert that metaphysics has always been pseudo-philosophy, from the pre-Socratics through Plato to medieval philosophy and Descartes? No, just as astrology was not considered pseudo-science during Ptolemy’s era or alchemy in Newton’s time. Today, however...

Fields of inquiry are not static. The philosophy versus pseudo-philosophy map should also incorporate a temporal dimension. Whether first philosophy has crossed into the realm of pseudo-philosophy is debatable. I contend it has, or is perilously close. Others maintain that their armchair musings genuinely reveal truths about the nature of existence. Regardless, this dialogue is invaluable, promising to enhance the understanding of all participants regarding the nature of their inquiries.

Chapter 2: The Nature of Pseudo-Philosophy

In this insightful video, "Karl Popper, Science, & Pseudoscience: Crash Course Philosophy #8," the relationship between scientific inquiry and pseudoscientific claims is examined. The discussion explores the criteria that distinguish genuine science from pseudoscience, using Popper's philosophy as a framework.

The second video, "It's all bullshit! On the similarities between pseudoscience and pseudophilosophy," sheds light on the parallels between these two domains, emphasizing the importance of critical thinking and empirical evidence in philosophical inquiry.